At the first legendary screening of his film Wavelength in New York in 1967, for about ten friends—among them Jonas Mekas, Ken Jacobs and Flo Jacobs, Amy Taubin, Nam June Paik, and Shirley Clarke—Michael Snow was still playing the soundtrack to the projection on an external tape recorder. Precise synchronization was not very important, although some sounds, such as the footsteps or voice of a performer, did relate to plot fragments on screen. Yet for all the interrelation of sound and image, Snow, who came to film from jazz (as well as from drawing, painting, and sculpture), wanted the acoustic and visual means of expression to remain independent of one another. Sound was by no means to be reduced to merely supporting the image.

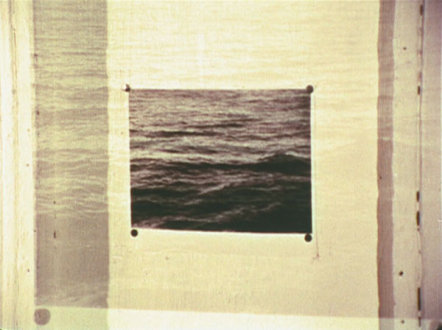

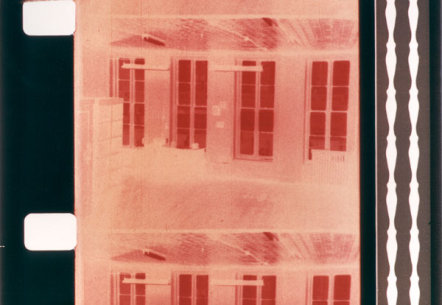

What one sees in Wavelength is a 45-minute-long, gradually narrowing interior view of a New York loft or, rather, of its windowed wall. The movement on film acts as a continuous zoom, from the opening wide-angle shot of the space to a close-up of a photograph of ocean waves that is pinned to the wall. On closer observation, this long zoom is revealed to consist of many individual sections, for the depth of field and exposure times of the respective spliced frames do not (exactly) match the edits. Shifts from daylight to darkness can be noted in places. Elsewhere, color filters or the use of a negative image interrupts the uniform sequence of events. Especially in the later parts of the film, long shots and close-ups clash abruptly. Along with the movements resulting from the hand-held camera and the editing there appear diverse fragments of a plot. First, two people, instructed by a woman, carry a cupboard into the loft. The woman returns later, accompanied by a second woman. One of them closes the window. At the same time, the static, which is possibly coming from the street, ceases. The other woman turns on a tape player, from which issues the Beatles song Strawberry Fields Forever. When the woman turns off the tape player, the music ceases; simultaneously, the previously heard static again becomes audible, although the window has not been reopened. Later, a man turns up and, shortly after entering the picture, sinks to the ground as if he has suffered a heart attack, thereby disappearing from the now narrowed image. Later still, a woman appears and tells the person on the other end of the phone line (who remains invisible to the viewer) that a dead man is lying in the room.

On the one hand, Wavelength includes sounds that (although they occur asynchronously in part) correspond to plot fragments, voices, and the aforementioned Beatles song. However, more extensive sections of the soundtrack, between the plot fragments, are taken up by the initially slow yet inexorably accelerating sine wave. The correspondingly constant rise in pitch finds its correlation on the visual level in the movement of the (more or less) continuously narrowing perspective. These two movements give rise to the film’s somewhat hypnotic effect, which serves both to foil and to catalyze its linguistic and semantic elements, such as the deconstruction of plot fragments and the discontinuity of the zoom’s progression. While the title of the film may be read as a reference first to the acoustic sine wave and second to light as modulated by the film, in the third instance it captures the irony of the photograph of ocean waves that fills the screen at the end of the film.